The following guest blog was written by Donato Calace, Vice President of Accounts and Innovation at Datamaran.

Donato Calace, Vice President of Accounts and Innovation, Datamaran

The conversation around materiality is evolving, and so is the language—we increasingly hear about double or dual materiality and dynamic materiality. But is it just semantics, or is there substance to the changes? And what does it all mean in practice for both corporates and investors? Are materiality practices shifting, alongside their definitions?

These are questions that companies will need to understand and answer. On July 22, I had the pleasure of moderating a webinar addressing these new perspectives on materiality. Guest speakers Jeffrey Hales, Chair of the SASB Standards Board, Lisa Epifani, Manager ESG Policy and Engagement at Chevron and Elisa Moscolin, Head of Sustainability & CSR at Santander, shared their views and experiences.

What is materiality?

Materiality is a concept that defines why and how certain issues or information are important for a company or a business sector. At its core, materiality is an accounting principle that defines which information is decision useful. Companies commonly use materiality assessment processes to identify issues that reflect an organization’s social and environmental impacts, as well as information that supports stakeholder and strategic decision making.

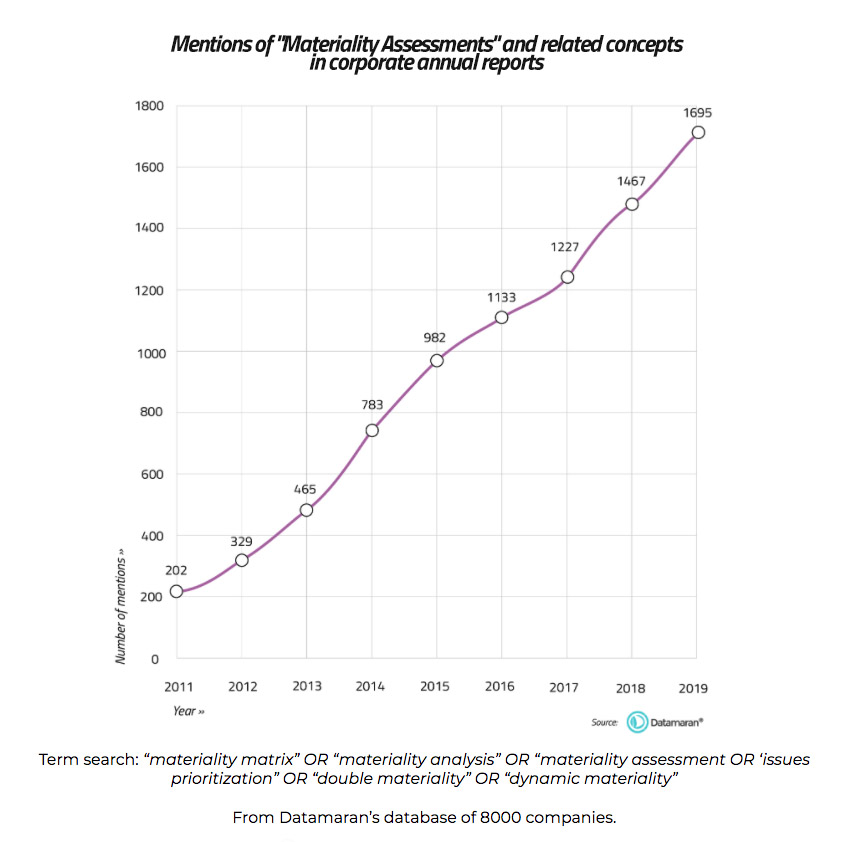

Over the years, the attention companies have given to this concept has increased notably: Datamaran insights show there has been a steady increase in the mention of materiality, including materiality matrices and processes, analysis and assessment.

“Companies do not succeed in isolation,” Moscolin said. “The very purpose of sustainability, ESG, and also materiality is making sure that they take into account their impact on the ecosystem within which they operate, and how that ecosystem impacts them. Only with this long-term view will they succeed—they won’t be short sighted or surprised by impacts that they hadn’t foreseen.”

Double and dynamic materiality: two different concepts?

The increased attention to materiality from a strategic point of view—hence involving senior executives—shows how this concept is not unique to the ESG space, and has concrete financial implications. Although companies have long assessed both the materiality of sustainability topics and the materiality of financial information, until recently they have rarely drawn a connection between these two concepts or their application. This consideration is well embedded in the perspective of dual or double materiality, which was introduced in regulation for the first time last July. The non-binding guidelines to the Non-Financial Reporting Directive clearly state that materiality is a continuum along which different issues, impacts, and information may fall and—perhaps more importantly—evolve. In other words, issues or information that are material to environmental and social objectives may develop to have financial consequences over time.

In fact, in July, when European Commission Executive Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis sent a letter mandating that the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) provide recommendations on EU non-financial reporting standards, he cited double materiality as a foundational principle for such standards.

By contrast, the concept of dynamic materiality, popularized this year by the World Economic Forum, emphasizes that there is a path for issues to become financially material over time and there are some triggers that make this process happen. It looks at materiality as a process that unfolds over time—and often very rapidly. This perspective is based on the consideration that what appears financially immaterial today can quickly prove to be business-critical tomorrow—as we’re seeing more than ever in today’s COVID-aware economic landscape.

Importantly, double materiality and dynamic materiality are interrelated concepts acknowledging different aspects of the same process; while the former describes more accurately how issues can be financially and non-financially material, the latter articulates the dynamics that drive an issue to move along the continuum.

From reporting to strategy: a necessary shift in the corporate approach

In light of the emergence of these new perspectives on materiality, SASB shared the standard setter point of view. As Hales explained: “Dual materiality and dynamic materiality are not new concepts, it’s just that there’s new language and an evolving understanding of these issues [that] helps to bring some clarity to frankly a concept that has been very challenging to communicate about for a long time.”

One key element of materiality is its specificity. As a process that creates decision-useful information, materiality links to a specific audience, Hales said. And it goes further: “Materiality is ultimately something that is entity specific; it is, in fact, situation specific.”

If materiality is specific to the company, its context, and its audience, how is it possible to set disclosure standards that are relevant?

SASB’s approach is to identify the industry-specific sustainability topics most relevant to business and investment outcomes, which it does through a process involving market consultation and evidence-based research. As part of the latter, SASB uses Datamaran to inform its standards development and benefit from the speed and accuracy that Datamaran’s AI engine provides in capturing real-time analytics on corporate, regulatory, and media developments.

The result of this process is 77 unique SASB Standards that provide industry-tailored metrics for the financially material subset of a starting “universe” of 26 sustainability issues. The Standards can thus provide a useful input to companies as they carry out their materiality processes, while ensuring the resulting disclosures are decision-useful to investors.

Ultimately, it’s up to corporate leaders to make strategic decisions about what is most relevant or not, and to design, implement, and maintain a transparent and defensible process to support these decisions.

Practical approaches to materiality

Beyond the nuances that each perspective involves, they share a central premise: materiality can and should be used not as a technical exercise, but to shed important light on business-critical matters for management, senior leaders, and even Board members. These insights should inform strategy and risk management, and need to be backed by data.

As Moscolin highlighted, data-driven materiality moves the conversation away from opinions about sustainability topics and toward facts and insights. It helps the company find value in the materiality assessment beyond reporting, and can facilitate consistency across three key business processes: risk management, annual reporting, and board reporting. “A solid, robust materiality assessment is incredibly important for reporting,” Moscolin said. “But I can’t stress enough how important it is that it’s used to inform your strategy.”

Similarly, for Chevron, adopting a dynamic materiality approach helps the company connect sustainability with risk management, and aims to ensure the board has oversight of the most pressing emerging risks. In this context, the company uses Datamaran, along with various processes, to, as Epifani explained, “help us streamline that research by identifying key issues, helping us find where peers are reporting, and looking at ESG reporting trends with solid data.”

To incorporate the new perspectives into a company’s approach to materiality, Epifani recommends, “A clear process that considers the ever-evolving and interconnected nature of ESG issues, a strong commitment to listen and proactively respond to your stakeholders’ concerns and expectations, and involvement from your executives and board.”

Why a dynamic materiality approach is business-critical

Although we have focused here primarily on the changing face of materiality in the ESG and non-financial world, these new perspectives should not be seen as part of the “sustainability niche”: materiality as an accounting principle is evolving more broadly. Taking a more dynamic approach is therefore critical for companies: the market is changing, the way key stakeholders—particularly regulators and investors—look at material issues is changing, and as a result, companies need to adjust accordingly.

With increasing interest in a dynamic approach to materiality, which requires continuous monitoring of sustainability issues backed by robust data, digital solutions can offer invaluable support, expanding the breadth of your analysis, enabling you to tap into a wider pool of stakeholder voices, and back-up decision-making with facts. To support companies on these goals, Datamaran helps companies track how issues change over time, with automated functionalities and an ontology—or list of topics—that evolves with and reflects today’s reality.

While materiality forms the foundation for reporting, there’s more to it: a robust process to assess the materiality of sustainability topics is data-driven and connected to governance mechanisms that involve the board and the C-suite, and, in turn, are indicative of a healthy company. As Moscolin said, “Using materiality for just reporting is a missed opportunity.”